November was a monumental month for United States immigration policy as the Trump Administration made great strides in fulfilling campaign promises to curb immigration. Off-hand remarks by President Donald Trump to reporters during a cabinet meeting revealed he was ending the Diversity Visa Lottery Program which has granted residency to 50,000 immigrants every year since its inception in 1990. The move comes as a response to the New York City terrorist attack of 31 October, in which 8 people were killed as a truck barreled through a busy pedestrian walkway. The vehicle was driven by immigrant Sayfullo Habibullaevic Saipov, an Uzbek that received a Diversity Visa in 2010. Just ten days after the Saipov attack, the State Department announced it would put an end to the Central American Minor (CAM) program, which aids children and young people. CAM, which granted refugee status to some 1,500 minors and eligible family members from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador since 2014, ended within 24 hours of the announcement. Additionally, Democrats in Congress are threatening a shutdown over the elimination of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, yet another measure to protect minors seeking refuge in the United States. Though unilateral initiatives like these may temporarily reduce the rate of legal immigration from volatile regions, they will do nothing to alleviate the economic and security pressures that cause migration in the first place.

Small Countries, Big Problem

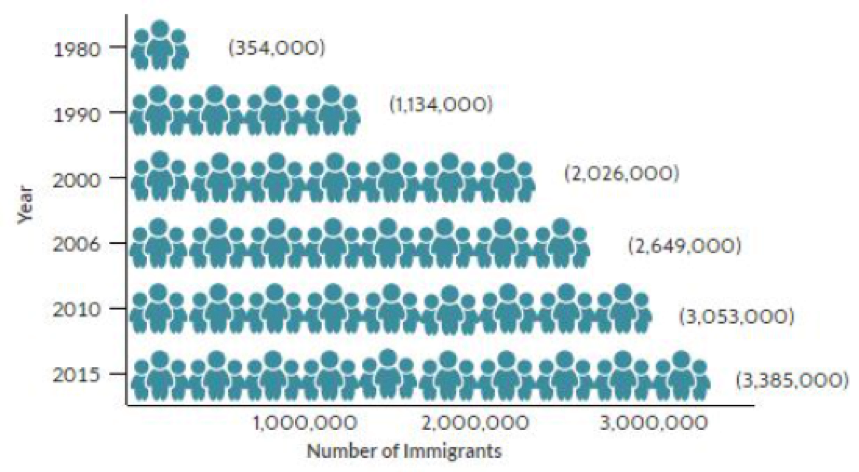

Despite the relatively small size of the countries involved, Central American immigration is a significant issue for the United States. In 2015, 3.4 million Central Americans resided there, representing 8% of America’s immigrant population. Of that group, approximately 85% arrived from only three countries: Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras—the area known as the “northern triangle” of Central America. Guatemala, the closest of the three and the one through which all Central American immigrants must pass, was the largest source country in the region, accounting for 27% all Central American immigrants to the United States in 2013. The rates of immigration have risen steadily in recent years as the economy in the northern triangle deteriorates. United Nations data from 2010 suggests more than half of Guatemalan emigrants left for economic reasons (33.1% to improve their employment conditions and 22.8% to obtain employment). Other top motivators include family reunification (12.3%), and to a lesser extent, concerns about citizen insecurity (2.9%). Poor economic conditions influence the decision to emigrate; lack of access to transportation, basic nutrition, and a level of income that makes it impossible to support families all influence the Guatemalan exodus. Tragically, the less-educated are more likely to make the journey, but less likely to have a real understanding of the risks involved or to have marketable skills that would help them earn more money in the United States. The problem is most pronounced among men; a staggering 47% of male Guatemalan emigrants have only an elementary school education level or less. Unfortunately, ethnicity also plays a factor. The demographic most likely to undertake the journey north is the country’s indigenous poor who account for 41% of the total Guatemalan population.

Bilateral relations with the United States are consistently among Central America’s most important foreign policy concerns. But those relations have soured over the past year as populist anti-immigration policies suggested Latin American immigrants present a direct threat to safety and security of American citizens. However distasteful the generalization of Latin Americans may be, the region has earned a reputation for instability since the mid-twentieth century. During the internal armed conflict of Guatemala (1960-1996), violence, political instability, and persecution led a large percentage of Guatemala’s population to seek asylum or refugee status in Mexico and the United States. Following the 1980s and the end of the conflict, political and economic instability subsided, but organized crime, gang violence, and the secondary effects of drug trafficking increased. The causes of Guatemalan emigration may have changed but the exodus continued.

Beauty and The Beast

Guatemala, thanks to its geography and various microclimates, is known as the land of the eternal spring. It is a country with fertile land for agriculture and is rich in coveted trade exports such as coffee and spices. Guatemalans enjoy access to both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, as well as a rich modern and ancestral cultural heritage as the center of the Mayan empire. What makes Guatemala’s situation tragic, however, is the paradox it presents. As is common in Latin America, a colonial past set the conditions for an elite-dominated society with weak institutions. When Guatemala achieved independence in 1821, lands were distributed between criollo families—those of full Spanish descent—endowing them with considerable political power and creating an economic and political class whose descendants manage the country to this day. This elite-dominated political system consistently fails to sustainably exploit the country’s resources, or squanders them through corruption and mismanagement.

For many Guatemalans, the only option is to seek opportunities elsewhere—primarily in the United States. There is an unofficial but well known route that leads from Guatemala into Mexico that then disperses migrants to the many possible entry points along the southern border of the United States. The journey can be a nightmare of hardship and danger, but one that many are willing to endure—a harsh indictment of quality of life in Guatemala. The most infamous leg of the journey involves transport on “the Beast” or “the Death Train”, named for the countless lives and limbs it consumes as migrants attempt to board the moving train in secret. Once aboard the Beast, migrants are vulnerable to grave violations of their human rights throughout their journey. Rape, extortion, kidnapping, and murder are commonplace; committed not only by the illicit agents that traffic migrants, but also by corrupt federal and state authorities whose paths the migrants cross.

For the Guatemalan migrants that successfully reach the United States, there is no guarantee of steady labor or prosperity. They typically find employment in restaurants, hotels, construction, and as domestic employees. Meanwhile, the are routinely subjected to discrimination and exploitation as they struggle to make minimum wage or worse. Central American immigrants constitute the largest percentage of immigrants working in the service industry, mostly because they lack the education and skills for higher-paying jobs. Despite this, remittances sent to families and loved ones in Guatemala are a crucial part of that nation’s economy. International Organization for Migration (IOM) data suggests that economic prosperity in the United States directly affects poverty rates in Guatemala. For example, the poverty rate in Guatemala rapidly increased after the economic crisis of 2008 and peaked in 2011. Regardless of changes to current immigration policy, the fortunes of the United States and its regional neighbors are inextricably linked.

Shared Problems-Shared Solutions

Despite the cold stance of the current US administration towards Central American migration, there are initiatives in both the United States Government and the international community, particularly the United Nations, aimed at helping migrants. Any person that holds an irregular status can seek assistance through technology-based information applications such as “Ask Immigration” or “MigrantApp,” a pilot program of IOM. These applications provide information about government services and answer questions related to immigration matters without the need for a lawyer or consultant. Western governments also have development programs to help Guatemala’s judiciary deal with the high number of criminals being processed by the courts. Programs like this address the root causes of emigration by contributing to rule of law and civil security, but do not address the dismal state of the economy.

Migration in North America is a regional problem and though international measures do help, success requires an effective United States policy that addresses the causes of immigration, not just its symptoms. The current US administration’s attempt to stifle the flow of migrants at the border by reducing legal immigration simply ignores the cause of the problem and promotes the illusion that the United States can somehow insulate itself from its southern neighbors and their respective domestic shortcomings. For its part, Guatemala and the rest of the Central America must increase job opportunities, strengthen their justice systems, and control illicit networks. Initiatives should be accompanied by social and cultural campaigns to discourage corruption, end discrimination, provide education, and address inequality. The way for Guatemala and the United States to control the flow of migration from the region is to improve the quality of life of those who would be most likely to leave. Comprehensive regional initiatives that strengthen economies and bolster citizen security are the long-term solutions to curb Central American migration and to stop feeding the Beast.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia also has experience working with human rights-based NGOs and is a regular contributor to The Affiliate Network.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia also has experience working with human rights-based NGOs and is a regular contributor to The Affiliate Network.

Major Kirby “Fuel” Sanford is a US Air Force Officer and F-16 Instructor Pilot with combat experience in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Major Kirby “Fuel” Sanford is a US Air Force Officer and F-16 Instructor Pilot with combat experience in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

eason we keep hearing tales of the group’s fabulous riches. Since

eason we keep hearing tales of the group’s fabulous riches. Since