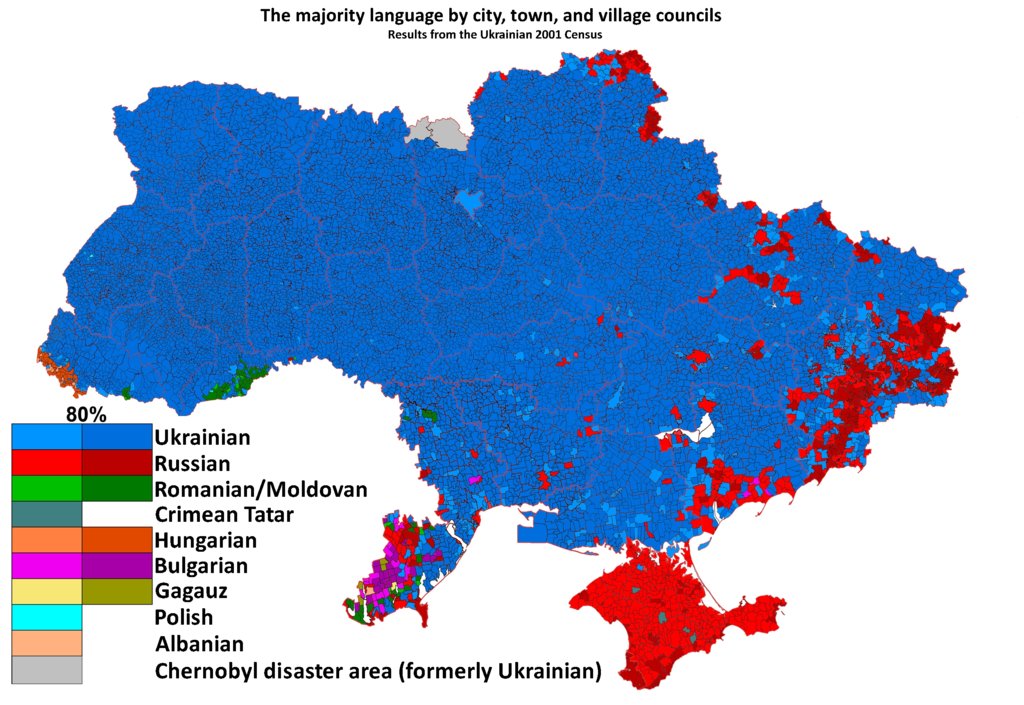

Russia has been fighting a war on Ukrainian soil since its “little green men” took over the Parliamentary building in Crimea in February 2014. The ongoing conflict, triggered by the flight of the Russia-backed President of Ukraine, has been very costly in human terms. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) estimated in a 2016 report that approximately 16,000 people have been killed or injured and around 2.8 million displaced by the fighting that continues despite two ceasefire agreements (Minsk I and Minsk II).

Even if the Minsk agreements are fulfilled, Ukraine will continually be at risk of Russian invasion. Kiev has very little control over its 1200-mile border with Russia and after years of neglect of its armed forces, Ukraine is at a great disadvantage relative to its large and well-armed neighbor. Clearly ignoring its previous commitments, Russia continues using its proxies to destabilize Ukraine’s eastern Luhansk and Donetsk regions and to maintain a corridor to Crimea.

In response, the United States and NATO have committed more than $600 million in non-lethal security assistance to Ukraine. This assistance includes training, advice for defense reform, and, according to the White House, defensive systems such as “counter-artillery radars, secure communications, training aids, logistics infrastructure, information technology, tactical UAVs, and medical equipment”. NATO provides advisory support, defense reform assistance, defense education, demining operations, and explosive ordnance disposal, and has created five trust funds to support Ukrainian defense. In addition, the US and Ukraine conduct two joint military exercises each year: SEA BREEZE and RAPID TRIDENT.

Russia’s actions and the collective response to it have led to a vigorous debate in western capitals about whether to respond by arming Ukraine. In 2015, citing an increase in ceasefire violations, a conglomerate of authors from three prominent US think tanks issued a report calling for the US to supply Ukraine with light anti-armor missiles and to give Ukraine three tranches of $1 billion in military assistance in 2015, 2016, and 2017. The Obama Administration, along with leaders of France, the UK, and Germany, opposed this course of action, but the apparent failure of non-lethal western aid to end the fighting is reenergizing some in the US Government to call for lethal assistance.

The Cost of Russian Aggression in Ukraine

Arguments in favor of arming Ukraine with defensive/offensive weapons emphasize security guarantees for relinquishing its nuclear arsenal under the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. Despite a Russian tendency to probe the international community for resistance before making risky decisions, the underwhelming response by the US and EU to Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 set a precedent in which the West settled for a frozen conflict. Proponents of arming Ukraine contend the West needs to send Moscow a clearer message about its involvement in former Soviet republics and the near abroad, a region Putin deems is his area of influence.

Additionally, Russia has been a participant in acts of war as well superficial attempts at peacemaking in Ukraine. Over the last three years Russia brokered ceasefires in conflicts to which it is a party and then violated those agreements for political purposes. This duplicity undermines international rules and norms and amplifies the security dilemma with many post-Soviet and Eastern European countries.

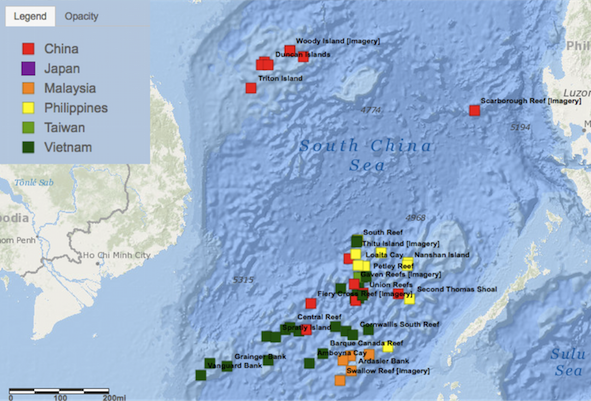

To those in favor of arming Ukraine, sanctions seem an ineffective way to alter Putin’s behavior despite a Russian economy in decline from falling oil prices. Russia’s naval base in Sevastopol, Crimea, one of only two warm water ports to which it has access, is strategically significant due to the presence of untapped oil and gas reserves off the coast. Russia has already illegally taken control of Crimean oil rigs and Putin may believe he needs a “land bridge” to the peninsula that would traverse East Ukraine through Mariupol. Lastly, Russia relies on defense manufacturing in the region that was once part of the Soviet Union’s sprawling defense sector.

To many, the arming of Ukraine is a logical next step in trying to force Putin to resolve the issue diplomatically. French and German leaders made numerous unsuccessful attempts to obtain a ceasefire and an agreement to end the conflict while the Americans brought violations of Ukraine’s territorial integrity to the UN Security Council as required by the Budapest Memorandum. Despite this, militants in East Ukraine have denied access to, threatened, and even fired upon OSCE observers. This blatant aggression seems to confirm the notion that Putin only understands force. Some observers cite recent research suggesting Russia uses tactics of bluster for political purposes and avoids risk in foreign policy endeavors. Western assistance through lethal defensive weapons could increase the risk level for Russia and help to call Putin’s bluff.

A History of Tepid Solutions

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the leaders of the UK and France oppose the idea of arming Ukraine. They note the importance of maintaining a coordinated response to Russian aggression to give validity and legitimacy to the West’s Russia policy. However, there will be difficulty obtaining consensus among all 28 EU member countries. Sanctions are a historical point of contention for economic reasons and because some countries are more reliant on supplies of Russian gas than others. Furthermore, arming Ukraine could prompt Putin to escalate the conflict, giving him a pretext for sending Russian troops overtly into Eastern Ukraine in much the same way he invaded Georgia in 2008. These points aside, if any further escalation by Russia is not dealt with forcefully by the US and EU, it would be a blow to western credibility and invite further Russian aggression.

The state of the defense sector presents a vulnerability for Russian aggression and an important opportunity for further western defense assistance. In 2016, the Poroshenko administration created a comprehensive plan for reforms based on detailed Rand Corporation recommendations for restructuring and strengthening the security and defense sector. Also in 2016, a former director of the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) became a special advisor to Ukrainian defense company, Ukroboronprom, for long-term development. While the industry is beginning to modernize and restructure, it remains relatively dilapidated with a distant prospect for tangible progress. The restructure of the Defense Ministry and General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, for instance, will not likely be completed prior to 2018.

Strengthening the Western Stance

The US and EU must determine realistic objectives for their actions. Bellingcat, an open source analytical organization that uses satellite imagery in investigating war zones, recently issued a report detailing what they purport to be evidence of cross-border shelling by the Russian government against Ukraine in 2014. Despite this, the West continues to accept the Russian argument that it does not need to be a signatory to ceasefire agreements or be held accountable for violating them. This charade is symbolic and useless at best; flippant and insulting to the West at worst.

Arming Ukraine with defensive weapons, a continuation of US policy under the Obama administration, seems to be the most prudent decision vis-à-vis Russia’s actions and the current state of Ukraine’s defense sector. However, for Ukraine’s long-term viability it may make more sense for the West to promote Ukrainian defense by advising and supporting the restructuring of its defense industry. Still, it is not enough. Aggressive and determined Russian actions in Ukraine require a definitive US strategy and better coordination with Europe, both of which are currently lacking. Until the West can settle the debate about how best to arm Ukraine, the fighting will continue on Russian terms.

Heather Regnault is a Ph.D. Student in International Affairs at Georgia Institute of Technology with experience in Kyiv, Ukraine. This article in no way represents the views of Georgia Institute of Technology, or the Faculty of the Department of International Affairs.