On 10 July, the tiny central African country of Burundi announced that its presidential elections, slated for 15 July, would be postponed by one week. The move marks the second electoral delay, and since April there have been protests, violence and a population exodus as the president postures for an unconstitutional third term. As one of the world’s poorest countries with limited strategic and resource importance, one has to wonder what the international community’s response will be should Burundi plunge back into the dark days of civil war and genocide. The moral lessons of history teach us that we must respond, but if historical events are any indication, it is unlikely that we will see much more than a token effort to restore stability in this part of the Great Lakes region.

Burundi’s Challenge

The events in Burundi have been coming to a slow boil over the past year and a half. Last year, President Pierre Nkurunziza’s party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy – Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) unsuccessfully attempted to reform the constitution in a way that would not only upset the balance of ethnic representation in government, but would also allow their leader to run for a third term. International condemnation was swift, however the CNDD-FDD persisted and announced Nkurunziza as their candidate earlier this year.

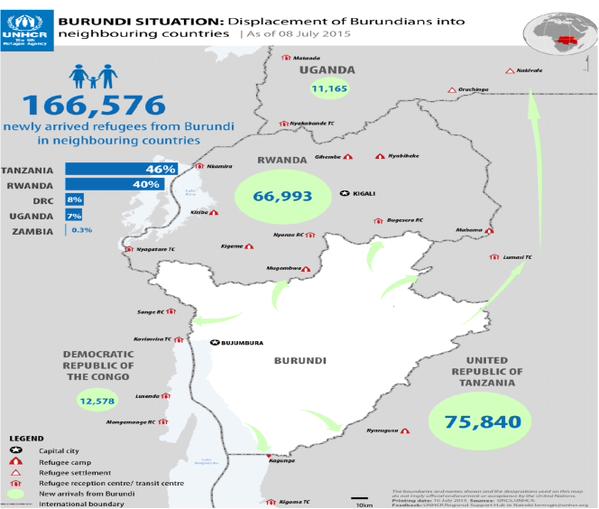

Public outcry and hostilities in Bujumbura quickly followed, and less than one month later members of the military attempted a coup d’etat while Nkurunziza was in Tanzania. Since then, ruling party supporters, to include the violent CNDD-FDD youth wing known as the imbonerakure, have sent scores of refugees fleeing into Burundi’s neighboring countries. According to Médecins Sans Frontières, one camp in Tanzania has swelled to 122,000, a number expected to increase as Election Day draws closer.

Last week on the international stage, United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon expressed “concern” over the compromised political and human rights environment unfolding in Burundi. The United States also condemns the ongoing violence and claims that it will “seek to hold accountable those responsible for gross human rights abuses.” Meanwhile, the Burundian Ambassador to the UN suggests reports of a rapidly deteriorating situation in his country (a place that only ten years ago emerged from a 12-year civil war that left 300,000 dead), are overblown. The most recent report from the UN states that we can expect more violence.

According to Burundian law, elections must be held at least one month before the final day of Nkurunziza’s second term, 26 August, and they cannot be pushed back again. This means that sooner rather than later, this Sub-Saharan country will enter a new phase of uncertainty and with stability in the country already compromised, the outlook does not look good. This summer Burundi already held parliamentary elections which the UN says were not free or credible. An increasing number of high level government officials, to include a Deputy Vice President, several electoral commissioners, and a senior judge—all citizens who do not agree with the ruling party’s measures—have fled for fear of being targeted as non-supporters of the CNDD-FDD.

An African leader aiming to overstay his term limits is nothing new, and indeed neighboring Rwanda faces a similar scenario in the run up to elections in 2017. As poor countries like Burundi experience upheaval as a direct result of this rule bending, the question then falls to the international community: how are we to respond? When does interference become a necessity in the name of safeguarding human rights? And if a response is needed, the more pertinent question must be pondered: will the international community be moved to act?

Never Say Never Again

I would argue that countries with little to offer in terms of strategic location and exploitable resources are the ones the world will most likely ignore. In Rwanda, a Central African country of comparable size and composition, the genocide of 800,000 Rwandans was completed over 100 days while the international community largely leaned back on its heels and watched from afar. The United Nations woefully under resourced its Assistance Mission For Rwanda (UNAMIR) from the beginning despite repeated requests for increased support by the mission’s force commander, Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire. When the atrocities finally saturated the world media, cries of “never again” echoed throughout.

The reasons behind the Rwandan genocide as well as the international community’s response to it are complex and not identical to what we see taking place today in Burundi. Still, the broader question of “How much should we care?” persists. If the situation reaches a point where Twitter becomes saturated with images of crimes against humanity, will there be a call to action? Big players like the United States are undoubtedly already asking themselves whether they have the political will, resources, and most importantly, any real regional interest to link arms with the international community and put a swift end to bad behavior. Sadly, I’m not so optimistic that we really ever mean it when we vow, “Never again”.

The United States, much like other asset-rich countries, is stretched thin as it battles enemies on multiple fronts in the Middle East and Central Asia. These campaigns speak nothing of the myriad other “fires” that currently rage on the African continent: Al Shabaab in east Africa, Boko Haram in the Lake Chad region and of course the Islamic State’s move into northern Africa. With so many other high-priority missions to tackle, does anyone really care about a tiny nation of 10 million that most Americans could never find on a map? Would the public really approve of troops being sent to a place that has no apparent impact on their day-to-day lives? Again, I am not so optimistic.

General Dallaire wrote in his memoir that he doubts the world will pay anything but lip service to these far off countries of little immediate consequence to the international community.

“We have fallen back on the yardstick of national self-interest to measure which portions of the planet we allow ourselves to be concerned about. In the 21st century, we cannot afford to tolerate a single failed state, ruled by ruthless and self-serving dictators, arming and brainwashing a generation of potential warriors to export mayhem and terror around the world. The leaders of the free world are well versed in the importance of regional stability, but it would appear that they are hedging their bets when they choose which ones they will assist and which they will supply with only a string of strongly-worded condemnation.”

The clock is ticking for Burundi, and as the hour draws near for their electoral moment of truth, there’s a good chance that the rest of the world, as they stand-by and watch, will face a moment of truth of their own.

Megan Hallinan is an active duty US naval officer who holds a bachelor’s degree in International Affairs from Trinity College in Dublin as well as a master’s in Nonfiction Writing from Johns Hopkins University. She lived for three years in Dakar, Senegal. The views expressed here are her own and not those of the US Navy.