It is hard to imagine a world where the United States is not the dominant global power. However, over the last decade the BRICS alliance (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) has emerged as a potential alternative to the traditional, US-centric power structure. In order to maintain its position as a global leader, the United States must effectively respond to the challenges presented by BRICS.

British economist Jim O’Neill of Goldman Sachs Asset Management developed the idea of BRIC in 2001 (South Africa joined ten years later) as an investment vehicle that took advantage of their large territory, abundant natural resources, and dense population. The BRICS nations leveraged O’Neill’s ideas to create the BRICS alliance to effectively leverage their combined strength. BRICS also provided each nation a platform to position itself as a regional power or as an international competitor of the United States. As BRICS continued to increase its presence in the international system, it presented an alternative to the traditionally western-dominated international power structure. There is a hope in some BRICS capitals, the alliance will accelerate changes to the status quo at the expense of the United States.

BRICS Economics

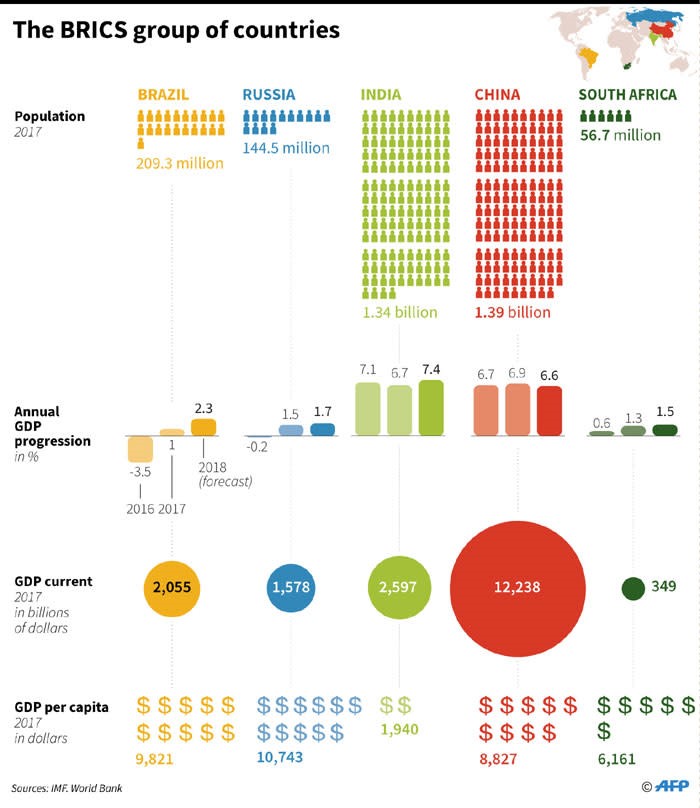

Without a doubt, BRICS is an international actor of significant influence. The BRICS nations represent 43% of the world’s population, 40% of its economy, 21% of the global GDP, and are responsible for 20% of global investment. According to the United Nations Development Program, the economies of China, India and Brazil will surpass the cumulative production of the G-7 in 2020. In 2014, in an effort to compete with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), BRICS created its own bank (the New Development Bank) and a framework for providing protection against global liquidity pressures they called the Contingency Reserve Arrangement. By 2018 the New Development Bank had lent US $7.5 billion, and this year it has issued bonds with a total value of 3 million yuan (US $447 million). These tools allow BRICS to operationalize the collective power of their economies.

Photo credit: http://www.granma.cu/mundo/2018-07-29/que-temas-se-abordaron-en-la-x-cumbre-del-brics-29-07-2018-20-07-13

BRICS is well-positioned to take advantage of the current state of international affairs and is expanding its political reach. The concept of “BRICS Plus” provides a political mechanism for non-member states to engage the bloc at its annual summit. In some ways, BRICS appears more stable than some European countries such as the United Kingdom that are in the midst of political or economic crises. Recognizing this and perhaps hedging their bets, Mexico, South Korea, Jamaica, Argentina, and Turkey have all taken advantage of BRICS plus and have attended BRICS events.

Photo credit: https://ewn.co.za/2018/07/25/brics-nations-by-the-numbers

Future of the Bloc

Despite success in its first decade of existence, BRICS must adapt to overcome today’s challenges. The trade war between China and the United States presents one such challenge. Additionally, controversial positions taken by the Bolsonaro government in Brazil — discrimination against racial miniorities, homosexuals, and women — complicate the aspirations of BRICS to present itself as a role model for developing nations. In order to continue serving as a key partner for developing nations, BRICS must provide tailored solutions that focus on commercial investment in those nations as well as the needs of the people and communities there.

BRICS member states have managed to overcome cultural and geographic differences to create a strong alliance. Together, they’ve laid the groundwork to achieve their collective goals of becoming a global economic force and reducing the effects of climate change. Jim O’Neill, the Goldman Sachs economist that conceived of BRICS, is certainly optimistic. He believes four of the five BRICS nations (China, Brazil, Russia, and India) will have the world’s dominant economies in 2050. In the last ten years, BRICS has already helped to redefine the international order. If the United States, and the western world more broadly, intend to maintain a dominant position in international politics and economics, they must begin responding to BRICS as a separate economic and political entity — an alternative alliance — not just a tiny piece of the foreign policy of its member states.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and is a regular contributor to The Affiliate Network.

Mefi Ruthviana Geary, PhD, has a scholarly interest in Countering Violent Extremism and deradicalization of terrorists. Her expertise is in Southeast Asian foreign policy analysis and open source intelligence (OSINT).

Mefi Ruthviana Geary, PhD, has a scholarly interest in Countering Violent Extremism and deradicalization of terrorists. Her expertise is in Southeast Asian foreign policy analysis and open source intelligence (OSINT).