Wearing full regalia to mark the 81st anniversary of Venezuela’s Bolivarian National Guard on August 4th, President Nicolas Maduro became the world’s most prominent target of a drone strike. The scene was typical of the farcical government theater Venezuelans have grown accustomed to over the last 19 years since Maduro’s charismatic mentor, Hugo Chavez was elected President. The small explosion occurred while Maduro was addressing a massive assembly of soldiers, firefighters, and police; seven of whom were wounded when two drones approached and dropped their ordnance near the procession.

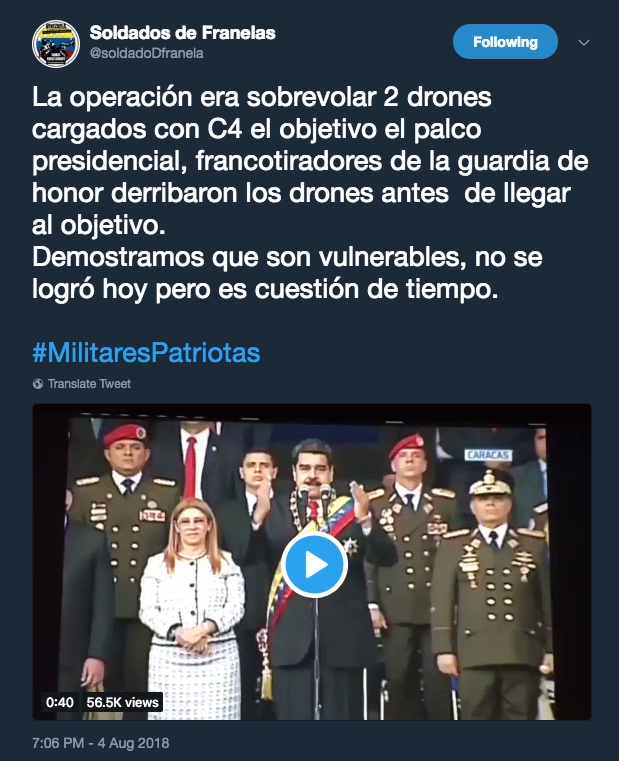

In a speech the following day, Maduro blamed the attack on the former President of Colombia, Juan Manuel Santos, a claim Santos bluntly repudiated. Though Maduro is accustomed to droning on against foreign interference, those claiming credit for the attack, a previously unknown group called “Soldiers of Flannel”, identify themselves as patriotic Venezuelans. They blame Maduro’s incompetence for the exploding economic crisis that is pushing millions of Venezuelans into desperation. Though some would like to write off the incident as a parochial Latin American squabble, the drone-delivery of explosives is a growing global security threat that simply cannot be ignored.

Bolivarian Devolution

Though Saturday’s drama may seem remote to those outside Latin America, Venezuela is in the midst of an exploding humanitarian disaster. This is not hyperbole. Some 1.5 million Venezuelans have fled the hyperinflation and scarcity that has plagued their economy since 2014. Conditions are at the point that international humanitarian actors supporting affected Venezuelans in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and elsewhere claim newborns in Syria have lower mortality rates than those in Venezuela. Once the richest nationality in Latin America, Venezuelans both at home and abroad suffer from malnutrition, crime, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking as the crisis — and their desperation — intensifies. Meanwhile, the Maduro regime increasingly relies on repression and violence to maintain control. A patronage system guarantees military and police loyalty but is coming under escalating stress from an inflation rate that may exceed 1 million percent by the end of the year.

At these rates, it is difficult to imagine Maduro will be able to sustain this system, particularly in the face of the rapid collapse of oil exports. For years, the state oil company, PDVSA, funded the socialist economy set up by Hugo Chavez; but as PDVSA demands for control of production grew to pay the rising costs of Chavismo, international oil companies began to cut their losses. Beginning with the American firms, the oil majors shut down their Venezuelan operations, taking their expertise and equipment with them and leaving a lasting impact on the economy, currency, and security of the country. Something will have to give in order for conditions to improve and Saturday’s drone strike suggests the security situation will further deteriorate long before the economy stabilizes.

Drones On Target

Saturday’s attack on Maduro, though of little significance in real terms, marks the first notable proliferation of non-state, drone-delivered explosives outside the Middle East. Though the attacked wounded seven members of the Bolivarian National Guard, Maduro was unhurt and he and the generals surrounding him responded stoically enough to preserve their machismo. What alarms security officials around the world about the incident however, is there is no real way to defend against this rapidly proliferating technology.

Drone technology has advanced by leaps and bounds in the last five years. Improvements in battery capability enabled this leap, driving down costs and giving smaller drones more range and power. Though state militaries were the early drivers of drone technology, they focused their research and development efforts on larger platforms that somewhat replicated capabilities of manned aircraft. Private hobbyists and commercial interests such as Amazon pushed demand for smaller devices and drove innovation faster than militaries were capable of doing. Not surprisingly, the commercial utility of drones as a delivery device has military implications as Mr. Maduro discovered on Saturday.

Keeping up with technological advancement is not the only policy challenge drones represent. In most parts of the world, airspace is only regulated above 3000 feet above ground level (AGL). Below that level, there are very few regulations and almost no laws governing air traffic. Even in those instances where governments made steps to address this gap, enforcement remains an administrative and technical headache. There are very few requirements for registration or licensing, and that’s just the start. On the extreme end of the spectrum, traditional defenses against air attack, specifically fighter aircraft and surface to air missiles, are almost completely ineffective below 3000 feet AGL. This is especially true in urban environments. Though one of the drones that attacked Maduro was reportedly shot down by an alert sniper, it crashed with its deadly payload into a nearby apartment building, setting fire to the structure and forcing an evacuation. The incident highlights that even effective defenses may cause unintended harm.

Technological solutions are no more promising. Countermeasures range from systems that jam guidance inputs, to others that launch netting to capture drones, to trained birds of prey. Clearly the defense sector is struggling to establish a workable industry standard. Detection is a different problem that has more obvious solutions but integrating them with countermeasures and backing that up with effective legislation and enforcement is the biggest challenge of all. If there is a silver lining associated with the dramatic attack on Nicolas Maduro, it is that his misfortune may actually raise enough alarm at a high enough level to make a difference. When it comes to drone defense, the Soldiers of Flannel said it best: “…it’s only a question of time.”

Lino Miani is a retired US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC.

Thanks to Kirby Sanford for consulting on flight rules and airspace control measures. Kirby is the author of Bolivarian Devolution and Paraguay: Voting Away Freedom on The Affiliate Network.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and