China has become a sensation in Western discourse, representing fears of economic displacement, military rivalry, and social upheaval. In many English language social media discussions about China, commentary can quickly escalate to the point that it is alarmist, ignorant, condescending, or racist. China is a vast country, with the largest population in the world, and they have experienced as much social, demographic, and environmental change in just the last generation as the West has in the last 100 years.

Despite what you may read in social media, analysis of China does not easily boil down to 140 characters or less. The “Middle Kingdom” is a vast land of contradictions, and much of what is said about the People’s Republic contain various levels of truth. An example of China’s extreme contrasts: although there is extreme poverty in many rural areas, Beijing just surpassed New York City in number of billionaires. Too often, commentators on social media try to dilute the facts into neat clichés and virtual soundbites rather than accept the complexities of the subject.

In an ever more globalized and interconnected world, words matter. Words and ideas compete for consideration and propagation on the internet. Opinions are shared, mimicked, and replicated quickly, often reaching unintended audiences, which is why so much commentary about China on social media is alarming. An opinion (educated or not) that is true to some extent in limited context can then be extrapolated and applied to other unrelated situations. The explosion of memes as acceptable political discourse on topics from the U.S. presidential primaries to the Refugee Crisis is a visible example of the problem of relying on social media for political information.

Where English language opinions are more informed, they are often limited in scope and origin to the expat enclaves of Beijing, Shanghai, and the Pearl River Delta, where Westerners can experience China without the polarizing filter of the media. Popular opinion is therefore a reflection of the shallow observations often repeated by our major media organizations, whose footprints in China are, at best, a field office in Beijing or Shanghai, and at worst, simply echo the opinions of the major papers.

The problem is, the Chinese people are listening very closely. Many Chinese leaders and thinkers view America as an example of a successful great power, and they seek to imitate that success while still preserving their socialist system. The U.S. is observed by many with near obsession, curiosity, and often with some degree of apprehension. Clearly unaware of the impact of their statements in social media, the last thing Westerners, and Americans in particular, should be doing is disparaging or dismissing arguably rational Chinese actions in the media.

Imagine two brothers, where the younger brother imitates the behavior of the elder. If the elder brother rejects and mocks him, how will the younger brother then act in the future? If the Chinese political and economic leadership do not feel like Americans respect them, they may change course and find another less palatable model for future development. The Sino-American geopolitical relationship is the most important one in the 21st Century, and the U.S. should not neglect its leadership role in the region through ignorance and careless internal public dialogue.

The Loud Voices in the Room

Here are some examples from social media to demonstrate the problems with careless internal dialogue:

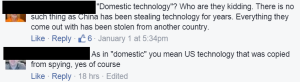

Opinion 1: The Chinese cheat (at business).

This type of message invokes a value of fairness, and claims that China is not playing fair: in business, military technology, etc… Allegations of cheating aside, consider that China has leapfrogged the industrial revolution right into the information revolution. While some would argue the fairness of China’s approach to modernization, it is nothing new. The idea of appropriating methods and technologies from more advanced nations has occurred over and over again throughout history as many now-developed nations also stood on the shoulders of the trailblazers who went before.

Sharing of intellectual property in jointly owned enterprises has been a condition of investment in China since Deng Xiaoping’s open door policy of 1980. Western companies have willingly entered into such agreements, making significant profits while American consumers benefited by being able to buy cheaper goods. Furthermore, a large number of Chinese businesses do not cheat and steal, so their reaction to such insults on social media is predictably and understandably defensive. Dismissive and disrespectful behavior on social media has serious potential to have a negative effect on the economic relationship between the U.S and China.

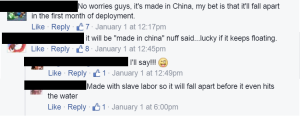

Opinion 2: Chinese products are terrible quality.

There is a lot of evidence to support the fact that some Chinese goods are low quality. There have been instances of fake milk powder tainted with hazardous chemicals, contractors reducing the quality of construction in schools, and “gutter oil” used for cooking, issues that have instigated mass social movements in China in response.

However, China as a nation is also capable of producing at high quality. The passenger rail system is not without flaws, but it has come an impressively long way. Most notably, the P.R.C. maintains a manned space program and in September 2013 sent an unmanned rover to the moon, which set the record in October 2015 as the longest operational lunar rover. When Westerners apply this opinion categorically, it becomes insulting and arrogant, asserting that the Chinese cannot do anything of quality, and the reaction is naturally negative with potential repercussions both in diplomacy and in business.

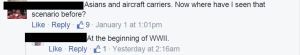

Opinion 3: China is a global threat.

The following comments came from a Facebook page on the People’s Daily discussing the ongoing fielding of the Liaoning, China’s new Ukrainian-made aircraft carrier:

This is an extreme instance of this opinion, where the commenter uses the anxiety around China’s rise to compare the P.R.C. to the Imperial Japanese, a comparison sure to promote defensiveness and hostility from Chinese readers. The memory of the brutal Japanese occupation is immortalized in film, monuments, and memorials throughout China, just as the communist resistance to the Japanese is celebrated as a legitimacy narrative. Tensions continue to run high between the two countries as was evidenced by the response to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to the Yasukuni Shrine in 2014. Arguable racist undertones aside, the commentary on China’s rise seems to swing to both extremes: Either China is a terrifying dragon, or China is a bumbling panda bear.

Rival or Partner?

If China is really a threat, then it could be a very serious one. When analyzing potential threats, analysis should be broken down into two components: capability of doing harm, and intent to do harm in the pursuit of a specific goal. Despite a large military, China has limited capability to threaten others in its immediate vicinity; the benefits of aggressive action are low and international connectivity makes the costs are still too high to make such policies palatable to the Chinese leadership.

The second component of threat analysis is often lacking in most Western discourse about China. Namely, do they even want to cause us harm? If/when they have the capability, would they want to use it? What would they achieve by doing so? Hostile and anxious comments about China shape and promote the kind of defensive hostility in China that the West does not desire. We should expect fear-mongering about China in the West to be mirrored, leading to further aggressive posturing and the increasing possibility of confrontation, perhaps leading to a fostering of the intent to do harm which does not currently exist.

An Avoidable Collision

Fear-mongering can be counteracted through education. The more accurate information is spread about China, the more we Westerners will realize the limitations of our knowledge. The Chinese people are awakening to the outside world thanks to the influence of the internet, but they remain rooted in their customs, history, and have their own unique challenges. Other countries need not consent to China’s strategic positions or praise their business practices. Understanding the Chinese in context, and cooperating or challenging as appropriate is the key. The current hostile and dismissive discourse is one avoidable factor unnecessarily escalating tensions between two civilizations which are leading towards an aggressive rivalry, rather than a rewarding partnership.

![]() MAJ Mike Kendall is a U.S. Army Engineer Officer with combat experience and extensive training in forcible entry and humanitarian relief operations. He graduated from Zhejiang University in Hangzhou China, and is currently attending the German Armed Forces General Staff College and Helmut Schmidt University in Hamburg, Germany. He holds a B.S. in International Relations, an M.S. in Engineering Management, and an MPA in Non-Traditional Security Management. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

MAJ Mike Kendall is a U.S. Army Engineer Officer with combat experience and extensive training in forcible entry and humanitarian relief operations. He graduated from Zhejiang University in Hangzhou China, and is currently attending the German Armed Forces General Staff College and Helmut Schmidt University in Hamburg, Germany. He holds a B.S. in International Relations, an M.S. in Engineering Management, and an MPA in Non-Traditional Security Management. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

eason we keep hearing tales of the group’s fabulous riches. Since

eason we keep hearing tales of the group’s fabulous riches. Since