Since the end of the Second World War, Europe has put its security in the hands of supranational organizations. These institutions, whether economic, military, or political, have deterred the wars between states that plagued European security since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. In that period, the march of uniformed armies decided conflicts and knowing where those armies were and how they were deployed was paramount to victory. For this there is no more powerful tool than an eye in the sky; satellite imagery in the hands of western governments. But today’s security challenges seem to invalidate collective intelligence systems.

Threats today are insidious. The massed armies of old have given way to environmental degradation, terrorism, and “hybrid” military threats designed to operate in the seams within Allied decision-making. Big states like France, Great Britain, and particularly the United States, hold a monopoly on imagery intelligence (IMINT) and distribute it through Allied intelligence structures at NATO and the European Union. With NATO’s Afghanistan mission winding down and a Euroskeptic administration in the White House, the old model of sharing IMINT is no longer flexible, responsive, or reliable enough to address the modern security needs of most European states.

A Transitioning Reality

The end of 2014 marked the transition from NATO’s United Nations-mandated International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan to Operation Resolute Support. The new mission focuses on building the capability of Afghan structures through training and financial instruments. These efforts are funded via the Afghan National Army (ANA) Trust Fund, the United States Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF), and the Law and Order Trust Fund for Afghanistan (LOTFA). The reduction of western troop levels and the primacy of Afghan institutions that cannot meet strict and expensive requirements for access to Allied intelligence, has reduced the urgency that previously drove the sharing of IMINT within NATO.

The election of Donald Trump may further restrict cooperation within NATO. During his first one hundred days as President of the United States, the Trump Administration made it clear it expects its NATO allies to increase their contributions to the organization. Though this is poorly defined and President Trump appears to be softening his position, intelligence sharing is not likely to increase during his administration leaving European allies to consider available options. Fortunately, advances in technology and the genius of the free market have generated alternatives in what was previously locked in the rarified world of classified military technology.

20/20 Hindsight

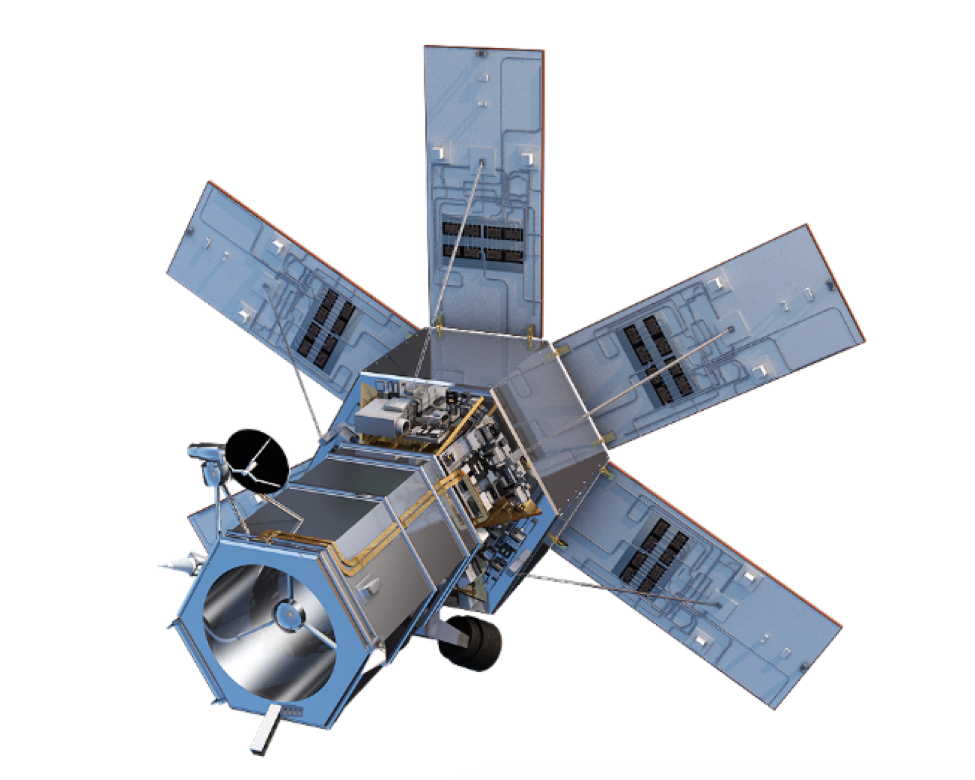

Commercial satellite solutions have come a long way since 1962 when the first privately sponsored mission sent the Telstar communication satellite into orbit. Today, high-resolution commercial earth observation and advanced geospatial solutions are useful across the many sectors of defense and intelligence, public safety, map making and analysis, environmental monitoring, oil and gas exploration, infrastructure management, and navigation. These options are inexpensive and rival legacy military capabilities in terms of resolution and coverage. When coupled with geographic information systems and internet technologies such as cloud computing and database management, commercial satellite imagery is a powerful tool in the hands of a growing community of potential clients.

Outlook for the Future

The Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom as well as the strong showing of nationalist parties in France, the Netherlands, Hungary, Poland, Greece, Turkey, and the United States are making it harder to implement complex supranational intelligence sharing arrangements. Terrorist attacks and the continuing influx of economic migrants and refugees continues to fuel growing discomfort with the risks inherent in “open door” policies. In this time of crisis, intelligence services, militaries, and police forces are under increased pressure to provide security and have already begun exploring unilateral solutions to the problem. Their task will be impossible however without the right tools for the job.

For now, European imagery comes from the combined abilities of the European Space Agency (ESA), the EU Satellite Centre (EU SATCEN), and the contributions of individual states. European leaders depend upon the abilities of the Copernicus Earth Observation program and the Sentinels to provide them with many of their imagery needs but these are legacy systems. The Copernicus constellation lacks the technological capability of newer commercial satellites like Worldview 4, and the nations are acutely aware of Copernicus’ shortcomings. For those countries lacking a space program or a military IMINT capability of their own, private sector solutions will be an increasingly important component in the defense and security of their nations.

![]() Johnathon Ricker is an account manager with Navisio Global LLC, CEO of Prospective International, and a student of international security, intelligence, and strategic studies.

Johnathon Ricker is an account manager with Navisio Global LLC, CEO of Prospective International, and a student of international security, intelligence, and strategic studies.