At eight o’clock on the morning of 25 November, 27,000 Philippine policemen and women went on alert ahead of the 30th Southeast Asia Games. At a press briefing from Philippine National Police (PNP) headquarters in Camp Crame, the spokesman for the Security Task Force, Police Brigadier General Bernard Banac, explained the practical implications of an alert this size. Leaves are cancelled or denied and overtime prepared for the multitude of officers required to secure the Games scheduled from 30 November through 11 December. Though the official figure of cops assigned to the Games was subsequently reduced to 19,767, they come from six federal agencies and countless local counterparts. The large size of the Security Task Force (STF) is a reflection of the scope of security challenges in the Philippines in general.

Less than three years since the Battle of Marawi, terrorism in the Philippines remains enough of a concern that the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) will play a significant role in guarding the Games. What Brigadier Banac did not mention was that special operations support often accompanies security preparations for events of this type and will come from a variety of sources. AFP Special Operations Command will certainly bolster the PNP Special Action Force for contingencies; as will other participating nations that will demand direct involvement with security of their citizens. Though it hasn’t been publicly acknowledged, world-class counterterrorism units from Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia are almost certainly involved with response planning if not actually deployed in the Philippines. Together, the combined forces of the STF and regional Special Operations Forces is a significant deterrent but it may not be enough.

Scope of the Problem

Securing the 30th Southeast Asian Games is a massive and expensive undertaking. The Games are taking place at 46 venues in four “clusters” spread across several provinces and thousands of kilometers. Four police regions – Ilocos, Central Luzon, Calabarzon, and Metro Manila – form the core of the STF. They are in turn supported by the AFP, the Bureau of Fire Protection, the Philippine Coast Guard, the Office of the Civil Defense, and the Metro Manila Development Authority, as well as local agencies from the four venue clusters. Recycling security measures used for elections, the PNP announced a ban on guns, sirens, blinkers, and “unauthorized motorcycle escorts” in and around the venues. These are significant expressions of state power, the management of which would be a significant bureaucratic challenge in the most developed of nations. In the poor, diverse, and criminally violent Philippines, it a daunting task.

Unsurprisingly, the largest effort by far is in the Metro Manila region. The National Capital Region Task Group of the STF consists of 17,734 of the total force structure. Though Manila is clearly the biggest and most visible venue and the most symbolically important, this leaves a scant 2000 personnel to guard and manage the remaining venue clusters in Subic, Clark, and “Other Areas” which includes significant events in La Union, Batangas, Laguna, and beyond. The Coast Guard contingent responsible for guarding the surfing events at La Union and other water sports in Subic and Zambales accounts for fully half of that number; a lopsided disposition that adds security concerns to the growing list of complaints about the Games.

Whatever the reason for the perceived (and real) dysfunction of the event, guarding the Games is a massive interagency – and international – security challenge.

Problems with the Games began well before the 30 November opening ceremony. Construction delays and shoddy work led to some events taking place in half-finished venues. There were reports of incomplete paint jobs, lack of lighting, and in the case of the first football qualifier, a stadium without a scoreboard or enough working toilets. Transportation and accommodation of athletes however provoked the loudest protests as several teams waited hours for transportation and were then forced to squeeze into accommodations designed for half their number. The Cambodian team became briefly famous for forcibly occupying their hotel’s conference room after being told there were no guest rooms for them. Ever active in the Philippines, social media exploded with comparisons to the disastrous Fyre Festival in the Bahamas and the hashtag #SEAGames2019Fail trended on Twitter.

Guarding Games

President Duterte is sensitive to the fact these complaints reflect poorly on the Philippines as a whole. Perhaps feeling pressure, he announced on 28 November that the military, not the police or a civilian planning committee, would organize future events of this type. In Duterte’s words, he prefers AFP planning because “they think structurally.” This is an unsurprising reaction from Duterte who has been predisposed to military administration for some time. In 2018, he placed the Customs Bureau under the AFP after elements of the former were involved in drug smuggling. At times he put the AFP and PNP at odds, encouraging the military to prevent corruption by blocking PNP officers from entering casinos. He has a pattern of appointing retired generals in positions of bureaucratic power. Eight of his Cabinet principals are retired generals as are 46 appointed to lower level offices. This includes the former Chief of Defense that serves as Director of the Security and Safety Cluster within the Southeast Asia Games Organizing Committee. With government in Manila largely in the hands of former AFP generals, it is difficult to pin the Games’ shortcomings on the failings of civilian planners.

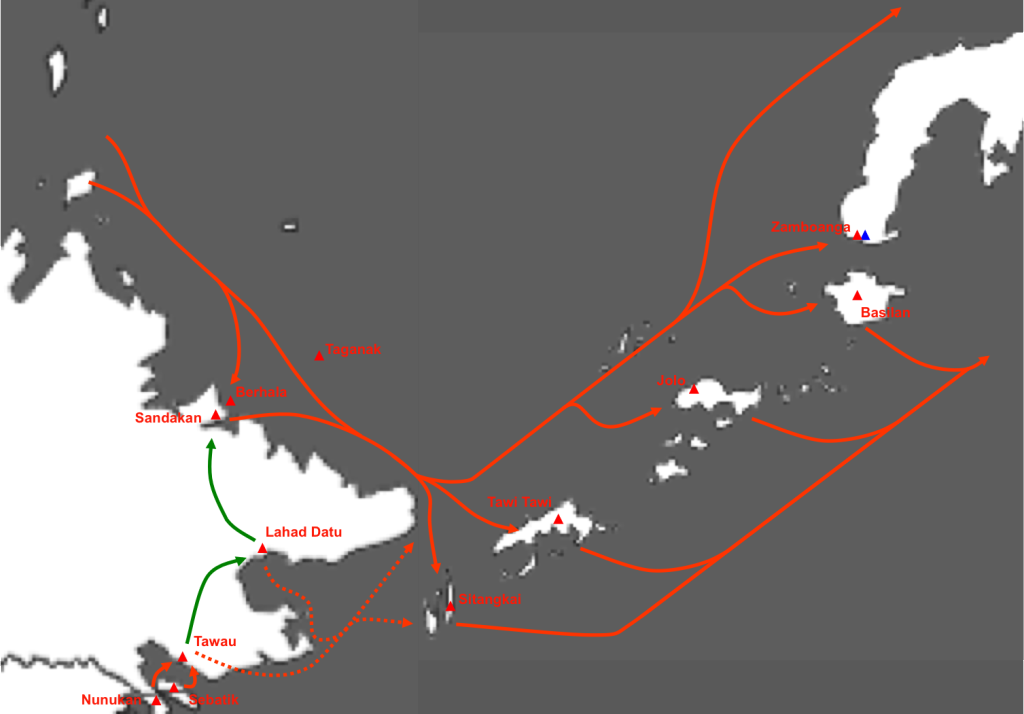

Whatever the reason for the perceived (and real) dysfunction of the event, guarding the Games is a massive interagency – and international – security challenge. Despite their best efforts however, the Philippine agencies tasked with security have limited funding and lack spare capacity. A number of powerful and longstanding insurgencies occupy the AFP in the country’s south while a well-armed criminal class empowered by the drug trade and enabled by entrenched corruption hampers the PNP’s ability to surge for the Games. The Philippine Coast Guard, charged with protecting the water sports, is well known for not having the budget to leave the pier. These obstacles are endemic to the Philippine government and are not likely to go away no matter how much “structural thinking” President Duterte manages to apply to guarding future games.

Lino Miani is a retired US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC.