Looking out upon the city from the top of a modern high-rise, one cannot help but note the contradiction. The urban sprawl of luxury apartments, malls, and cafés gives way to the eclectic but destitute clusters of favelas; the multi-colored and corrugated steel-roofed slums that dominate the periphery. The city is Rio de Janeiro, but it could easily be Lima, Peru, Buenos Aires, Argentina, or Bogotá, Colombia. This caricature of rich-meets-poor ambiguously describes nearly every major city in Latin America, a region in which a growing number of countries occupy the margin between developed and developing status.

The global trend of urban migration is particularly strong in Latin America, compounding development shortfalls for safe and adequate housing in capital cities. In Rio, for instance, 1.5 million people live in the favelas—about 24% of the population. There are over 1000 of these neighborhoods in the city, the majority of which are illegally constructed. Brazil is the region’s largest country, economy, and the presumptive regional hegemon, but like others in the region they struggle to spread the benefits of growth to all socioeconomic classes. Nearing the milestone of developed status, Latin America is starting to question exactly what developed truly means.

Development by the Numbers

The World Bank sorts countries of the world into four income categories: low income, lower middle-income, upper middle-income, and high-income countries. Half of the world’s countries fall into the two middle-income categories, which contain 70% of the world’s population and 72% of the world’s poor. All low-income and middle-income nations are eligible for Official Development Assistance (ODA)—the collective non-military aid, grants, and financial instruments intended to promote economic development and welfare—which totaled $142.6 billion dollars in 2016.

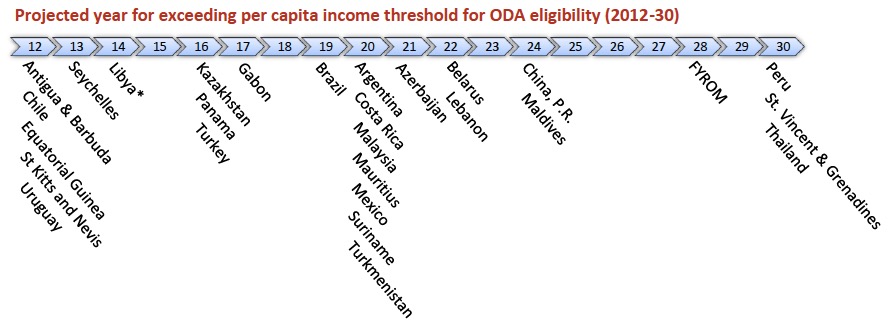

Once middle-income nations reach and maintain a per capita Gross National Income (GNI) of $12,745 USD or greater for three consecutive years (2013 numbers), they “graduate” from upper middle-income status to high income status, rendering them ineligible for ODA. Latin American ODA totaled nearly $5 billion dollars in 2016, but sable growth within the region over the last 25 years places countries such as Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico—those with large populations and high inequality—on a path to graduation from ODA eligibility.

The body that determines these categories is the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The DAC, in conjunction with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, meets every two to three years to refine the list of eligible aid recipients. Middle-income countries constitute 90% of Latin America, and by the year 2030, 80% of the region will no longer be eligible for ODA.

The first wave of this phenomenon hit the region in August when Chile, Uruguay, and Costa Rica graduated to high-income country status. The graduations come after a period of GDP growth in the region averaging 3% between 2000 and 2015. In countries like Brazil and Argentina, next on the list of prospective graduates, poverty has decreased drastically since the turn of the century. According to the World Bank data, poverty in Brazil decreased from 12.3% in 2002 to 3.7% in 2014. Argentina’s poverty level fell from 14% to 1.7% over the same period.

But these indicators only reveal part of the story. The World Bank international poverty line is drawn at $1.90 dollars of income per day, or about $685 dollars per year. Inequality figures in the region are the highest in the world. The 2016 Gini Index—the measure of statistical indicators that assign a value to inequality—show Latin America occupying 13 of the top 25 spots for highest inequality in the world. The top 20% of the population still holds 57% of the wealth and it has the fastest growing number of billionaires in the world, numbering 151 in 2015, a 38% increase over the previous year. Given that context, reaching the $685 dollars per year milestone seems to leave much room for improvement.

Graduate to Cooperate

The steady loss of ODA will be Latin America’s next development challenge, and the millionaires and billionaires will not be the ones feeling the impact. Chilean government officials have already been vocal in their objection to the graduation process, arguing that the loss of ODA comes at the most critical point for developing nations. They contend that the process is one-dimensional and does not reflect the complex set of issues that countries in this category face in sustaining development. This is true, but many of the challenges come from within Latin American governments and cannot be solved with ODA. Tax systems are archaic and welfare programs, especially in a non-welfare state like Chile, are limited or not sufficient to bridge the gap of inequality.

The real implications for ODA graduation are unknown. The OECD lacks the requisite data to be able to predict how ODA graduation affects future development. Additionally, development assistance varies from year to year, is given at the complete discretion of the donor countries, and is subject to global foreign policy trends. A retraction in globalism, increases in terrorism and security concerns, and global migration and refugee flow will continue to influence the distribution of aid. As countries in the global south continue their efforts in development, relying on ODA cannot be the only strategy to sustain development.

One opportunity lies in increasing South-South Cooperation, characterized as a framework of collaboration across multiple domains between countries of the global south. South-South Cooperation focuses on the transfer of knowledge, technical expertise, and human capital—all critical components of development. This collaboration already exists in the region, but the programs are few, the level of institutionalization is low, and domestic and regional politics often hamper cooperation efforts. Unlike the regional bodies (like MERCOSUR and UNASUR) that have high levels of institutionalization with low output, South-South Cooperation is accomplished through existing, state-level institutions like a country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This allows them to engage in programs on a limited or enduring timeline, bilaterally or multilaterally, at both the national and sub-national levels.

Latin America—and the global south in general—must seek internal solutions for development. They will also need to find a way to better incorporate NGOs and the private sector, who have an increasingly important role to play in the global system. Regional economic leaders, such as Brazil, Chile, and Mexico, can accelerate the pace of regional cooperation initiatives and counter the loss of ODA over the next decade. Bureaucratic inefficiency and corruption make reforms difficult, but South-South Cooperation provides an existing framework and support from the United Nations Office of South-South Cooperation (UNOSSC). A failure to reform and generate intra-regional development programs may not slow economic growth, but it will threaten future social and political stability and undermine long-term regional security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of any government or private institution.

Major Patrick “TISL” Parrish is the Blogmaster and editor for the Affiliate Network. He is a US Air Force Officer and A-10C Weapons Instructor Pilot with combat tours in Afghanistan and Libya.

Major Kirby “Fuel” Sanford is a US Air Force Officer and F-16 Instructor Pilot with combat experience in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Major Kirby “Fuel” Sanford is a US Air Force Officer and F-16 Instructor Pilot with combat experience in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.