This article has been republished with permission from our partner, Stratfor. The original version was first published in Stratfor’s WORLDVIEW and can be found here.

Highlights

- Beset by infighting, the ruling African National Congress is incapable of effectively tackling the country’s worsening economic and social situation.

- Those problems will drive more highly skilled individuals to emigrate, robbing the country of productive workers and tax revenue in the years ahead.

- Deepening economic malaise and internal fissures will accelerate the erosion of the ANC’s once-dominant electoral position, possibly opening the door to more extreme parties, with serious policy implications.

- As South Africa struggles to get its house in order, its influence over the rest of southern Africa will wane.

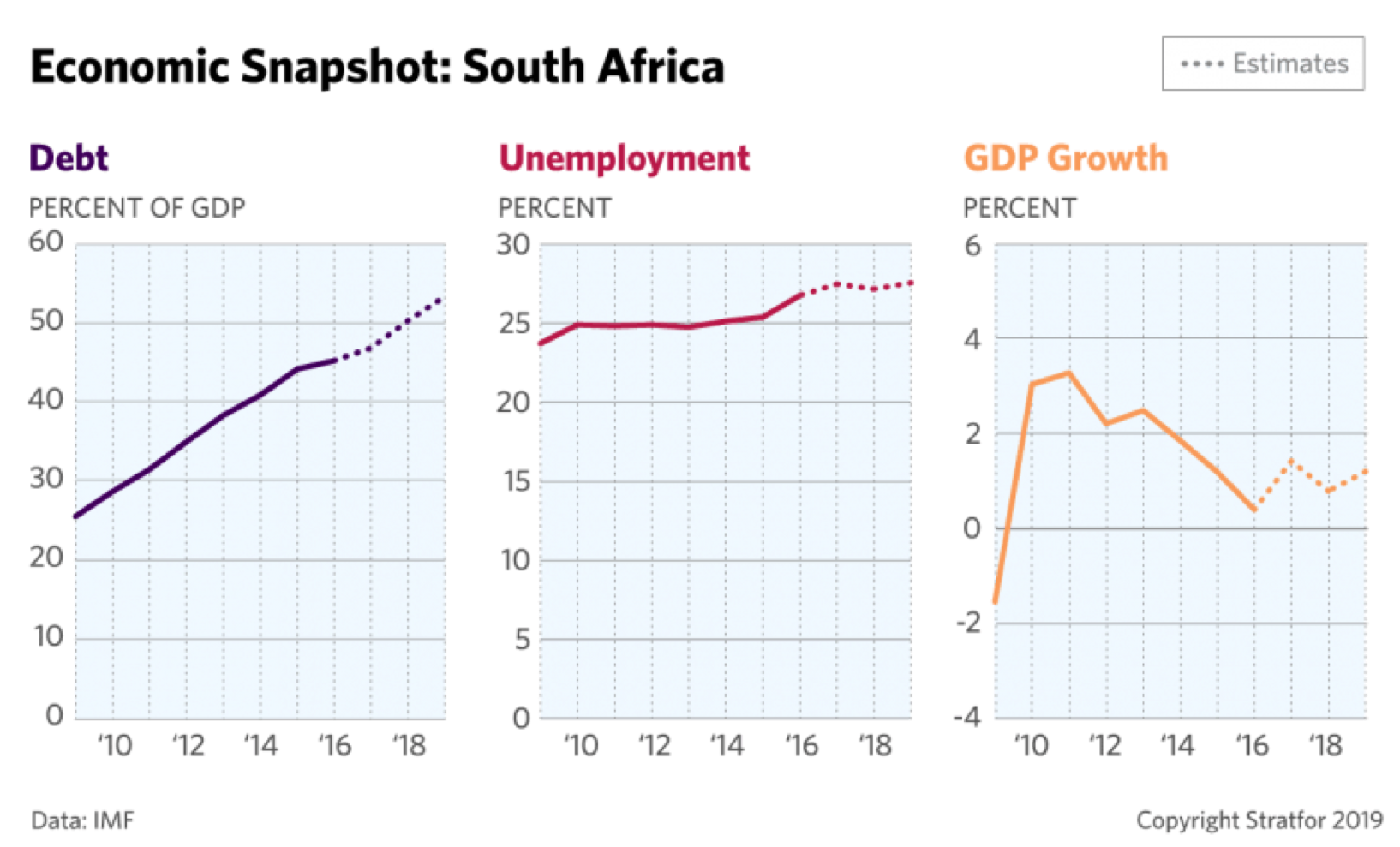

“We are sorry for what happened,” South African President Cyril Ramaphosa told a group of workers earlier this month in Durban. “Our image, our standing and our integrity [were] negatively affected.” Ramaphosa offered the heartfelt mea culpa following yet another wave of xenophobic riots across South Africa, yet presidential apologies are unlikely to stanch more violence directed against foreigners there — or cure the deeper malaise that drives the unrest. That’s because successive governments in Pretoria have failed to foster essential economic growth in South Africa, which posted an eye-popping unemployment rate of 29 percent earlier this year. Every week, thousands of its citizens are forced into unemployment or underemployment in the extensive black market.

The Big Picture

Years of economic and social woes have taken a toll on South Africa. As the country grapples with yet more indications of weak or negative growth, sky-high unemployment, massive crime rates and coming political change, its ability to remain a continental economic powerhouse will be under threat.

See 2019 Fourth-Quarter Forecast

See Sub-Saharan Africa section of the 2019 Fourth-Quarter Forecast

And it’s not just joblessness that is eating away at the rainbow nation; a host of other factors are driving home the severity of the country’s crisis: rising government debt, crumbling infrastructure, collapsing education standards, rampant crime and violence, currency volatility, investment outflows, and more. Together, it’s given rise to the sentiment that South Africa is increasingly a country of “haves” and “have nots,” tearing at the country’s social fabric, resulting in mass alienation and disenchantment with the political system. And with the ruling African National Congress (ANC) seemingly unable to get its own house — let alone South Africa’s — in order, the continent’s powerhouse will go through plenty more trials and tribulations before it sees any glimmer of hope.

A Battle Over Spoils

In spite of ever-worsening economic and social problems, the ANC government is incapable of implementing drastic and fundamental reforms to jump-start growth, offering instead “pie in the sky” policy rhetoric that has failed to translate into reality. At the heart of the problem is the ANC itself: The party is riven by massive internal factionalism. In the years immediately after apartheid, ideological differences may have driven the party’s divisions. But since then, the ANC has become mired in corruption and mismanagement, with the effects becoming evermore pronounced in recent years. In effect, the main battle brewing inside the ANC today centers on access to money and resources; policy differences, ultimately, are largely irrelevant. South Africa’s economic boost during the global commodity supercycle driven largely by Chinese demand in the late 2000s obscured this internal conflict and its negative impacts until the good economic times ended in 2014. Since then, bleaker prospects have challenged Ramaphosa and his allies’ efforts to turn around the party and government through anti-corruption efforts, in part because he must contend with other powerful factions — most notably those aligned with his predecessor, Jacob Zuma — that benefit from his administration’s failure to root out graft at all levels of government.

This has serious policy implications. Given Ramaphosa’s flimsy coalition against other ANC factions, the president cannot robustly push “controversial” economic reforms which, in the South African context, entails market-based reforms that demand increased efficiency. For starters, these limitations have hindered Ramaphosa’s goals of overhauling the country’s embattled public utility company, Eskom. After nearly scuttling the South African economy last summer amid blackouts that it instituted to protect the unstable electrical grid, Eskom has already sucked up billions of dollars (necessitating ever-mounting debt) in 2019 to keep the lights on. Unsurprisingly, there is little sign of an improvement in store.

Despite the gravity of the situation, several of the country’s powerful unions have vowed to turn on Ramaphosa if he seeks to turn around Eskom by either privatizing the utility or laying redundant workers off. (According to the International Monetary Fund, Eskom’s workforce is bloated by a whopping 66 percent.) Should Ramaphosa opt not to alienate the powerful labor leaders who paved his path to the top of the ANC in 2017, he will have few policy options with which to deal with Eskom. In the end, one thing is certain: Failing to fix the company risks plunging South Africa’s economy into more crisis. As one Eskom board member recently warned, the current electrical grid cannot handle even a relatively minor uptick in economic activity without experiencing a system meltdown.

Despite the gravity of the situation, several of the country’s powerful unions have vowed to turn on Ramaphosa if he seeks to turn around Eskom by either privatizing the utility or laying redundant workers off. (According to the International Monetary Fund, Eskom’s workforce is bloated by a whopping 66 percent.) Should Ramaphosa opt not to alienate the powerful labor leaders who paved his path to the top of the ANC in 2017, he will have few policy options with which to deal with Eskom. In the end, one thing is certain: Failing to fix the company risks plunging South Africa’s economy into more crisis. As one Eskom board member recently warned, the current electrical grid cannot handle even a relatively minor uptick in economic activity without experiencing a system meltdown.

Over the Cliff

The long-term implications of years of ANC-led mismanagement loom large. For one, recent data proffered by an emigration services company, Sable International, strongly suggests that an exodus of South African individuals with a high net worth, as well as highly skilled workers, is underway. This, naturally, will have consequences as South Africa continues to rely more heavily on its shrinking tax base for government revenue. In addition, the flight of highly skilled workers will affect key sectors in global demand, like healthcare and high-tech, robbing the country of the more productive segments of its society. Most troubling for the government, data shows that the vast majority of these individuals do not return to the country once they emigrate.

Pretoria’s inability to make the tough policy choices to alter course will ultimately result in the country’s economy continuing to take on water. With weak or negative growth projected for the next several years, unemployment will remain high, resulting in yet more misery, high crime and violence. And in addition to Eskom’s woes, the country’s water systems, public transportation, waste management and other critical infrastructure will further deteriorate, pushing the costs and consequences onto its citizens. This, in turn, will encourage more highly skilled workers to leave the country for greener — and safer — pastures. South Africa’s political elites will find this downward spiral difficult to break, paving the way for the country to lose its ability to influence its much smaller neighbors. And as the author R.W. Johnson has pointed out, unlike the case of Zimbabwe — which sent millions of economic migrants over the border to South Africa when its economy collapsed — South Africans trying to escape economic misery have nowhere else in the region to go.

By the time the country’s leaders receive a stronger popular mandate to remedy its dire situation, South Africa will be in a far deeper hole with far fewer human resources to help dig it out.

This constraint on mass emigration will create an increasing number of disaffected voters who will erode the ANC’s once-dominant electoral position. Amid the economic stagnation and political infighting, younger voters who have few memories of the ANC’s struggle against apartheid — and, thus, little loyalty to the party — will look for other options come election day. Quite when the ANC will lose its political predominance is an open question, but South Africa’s poor economic trajectory and the ANC’s internal squabbling mean that a sea change will come sooner than later.

Ultimately, the impact of the ANC’s eventual reckoning will depend greatly on which political parties step in to fill the political void. For example, a weakened ANC that loses its majority will likely have to join an alliance with another major political party — an act that in itself that will likely accelerate the ANC’s breakup as dormant ideological debates erupt and battles over resources lead to a final splintering. Accordingly, does the future ANC opt to align itself with the far-left Economic Freedom Fighters? If so, the impact would be huge. To begin with, such a partnership would cause a sharp left turn in the country’s policies, resulting in the accelerated transfers of wealth to the impoverished black majority (at a huge cost to market efficiency). Policies like these would spook foreign investors, increase the brain drain, cause capital flight and send South Africa-based corporations scattering to other major African hubs. Relatedly, it would turn Pretoria’s focus away from the rest of the continent, thereby speeding up South Africa’s decline as a regional economic and political power (with no country in the region likely to assume its place).

An uneasy future alliance with the center-right Democratic Alliance could push the ANC into adopting more market-based policies. However, this scenario would be no panacea, as it could only occur if it receives serious political backing from voters who have otherwise favored populism over market efficiency. (What’s more, it would also likely usher in the ANC’s fragmentation into splinter parties, greatly upending the political system.) Popular support for tougher market reforms is only likely to come after more years of economic and social woes. By the time the country’s leaders receive a stronger popular mandate to remedy its dire situation, South Africa will be in a far deeper hole with far fewer human resources to help dig it out.

Amid its political leaders’ inability to pursue the tough policy choices needed to address the country’s growing socio-economic crisis, South Africa is sinking. The result, for the time being, will be the increase of internal strife and policy uncertainty, the erosion of the country’s economic base, and the loss of its regional hegemony. The only question, then, is just how stern South Africa’s reckoning will be.

Stephen Rakowski is a Sub-Saharan Africa Analyst at Stratfor, where he monitors political, security and economic trends unfolding across the continent. Mr. Rakowski holds a master’s in government with a focus on diplomacy and conflict studies from the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya in Israel. He also holds a bachelor’s in international relations from Franklin University Switzerland in Lugano, Switzerland. In addition to his studies, Mr. Rakowski has traveled and lived throughout Madagascar, Morocco and Kyrgyzstan.

Stephen Rakowski is a Sub-Saharan Africa Analyst at Stratfor, where he monitors political, security and economic trends unfolding across the continent. Mr. Rakowski holds a master’s in government with a focus on diplomacy and conflict studies from the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya in Israel. He also holds a bachelor’s in international relations from Franklin University Switzerland in Lugano, Switzerland. In addition to his studies, Mr. Rakowski has traveled and lived throughout Madagascar, Morocco and Kyrgyzstan.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and