Catastrophic Success: A humorous term describing an ironic situation where one unexpectedly achieves all of his or her unlikely objectives.

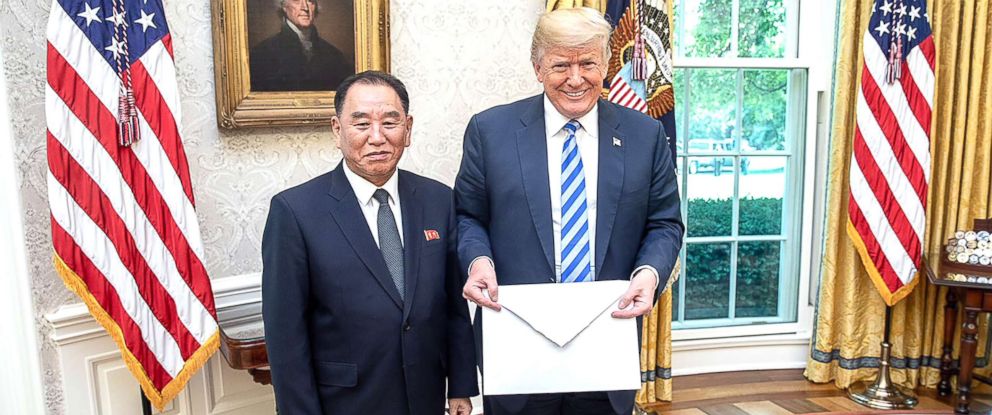

The cynical humor of the term “catastrophic success” is not typically found in reference to international relations, but on June 12th, the President of the United States of America is hoping against hope to achieve exactly that in his meeting with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. Indeed, Mr. Trump will become the first person in his position to meet with a North Korean leader. Though the White House is presenting the meeting as a historic “summit” between world leaders, there are a number of reasons why none of Mr. Trump’s predecessors ever attempted such a meeting. The stakes are high and the many risks are well known…except one: Any success short of the catastrophic variety may actually do more harm than good in the long run.

The Non-Summit

Any discussion of the so-called “summit” between Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump should begin with a review of why Korea was divided in the first place. On 8 August 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan in what was both a show of Allied unity and an opportunistic power grab. Recognizing the strategic importance of the Korean Peninsula, America and the Soviets – and their Korean counterparts – invaded the Japanese stronghold from both the north and south and met roughly in the middle near what is now known as the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Following Japan’s surrender, the United States and the Soviet Union agreed to sponsor an election to determine the future leadership of an independent Korea. Though United Nations General Assembly Resolution 112 captured this intent, Cold War tensions escalated to the point where the North Korean contender, Kim Il Sung, refused to hold an election and repudiated the victory of Syngman Rhee in the south.

Following the July 1948 election, the United Nations quickly declared Rhee the legitimate president of all of Korea[1], to which the Soviets responded by declaring Kim Il Sung Prime Minister of the north. This is an important point. The UN recognized the government in Seoul as the only legitimate government on the Peninsula in 1948 while the Soviets only declared Kim’s sovereignty north of the DMZ. The result is history. Within two years, Soviet-sponsored North Korean troops poured over the border. The eventual military stalemate crystallized the division of the Peninsula at the DMZ and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) was born. When the smoke cleared, 36,000 American, 230,000 South Korean, and 3200 other Allied troops lay dead along with 600,000 South Korean civilians in a war fought specifically to deny the aspirations of an illegitimate pretender to the throne of Korea. Kim Jong Un has simply never been a head of state.

Korean Conundrum

Kim’s illegitimacy and the resultant suffering it caused is the reason no sitting US President has ever agreed to meet a North Korean leader or even to hold bilateral talks with DPRK. To recognize Kim as a head of state would legitimize the division of the Peninsula and invalidate the sacrifices made by UN forces from 1950 until today. Though this makes President Trump’s “summit” with Kim Jong Un deeply troubling, it is true we will need to move beyond the past in order to achieve peace. However, the negative effects of Trump’s approach are not just symbolic, they may actually make peace less likely. Depending on which Trump statement about the “summit” one believes, its objectives include the very worthy goals of denuclearizing the Peninsula and reaching a negotiated end to the Korean war. Even if those goals were achievable – doubtful at best because they involve numerous stakeholders – they are even less likely now that Trump has unwisely elevated Kim to head of state.

The question of leadership is the very reason for the Korean War and resolving it is critical to any future hope for an agreement. Where before there was only one legitimate head of state, there are now arguably, two. The original post-war question of who should rule Korea is now complicated immensely by the fact that the United States has abandoned any clarity on who it supports for the task. Elections will not settle the matter because, like his grandfather, Kim Jong Un knows he cannot win and will not participate. Unlike his grandfather however, he has nuclear weapons to ensure all the stakeholders consider his opinion.

The likely outcome of the ill-conceived and rushed Singapore “summit” is that Korea will be left with a more difficult road to peace; a brutal dynastic dictator with increased negotiating power to legitimize his nuclear arsenal; and a South Korean government that has now lost its claim to sovereignty over the rest of the Peninsula. As we watch – with a mixture of hope and trepidation – the bizarre Trump foreign policy play out in the city-state, let us hope for catastrophic success because anything less may be simply…catastrophic.

[1] More precisely, the UN declared Rhee the legitimate president of those areas that held elections verifiable by the UN; i.e. the South, but also stated his government was the only legitimate governing body on the Peninsula and demanded its authority be extended to the entire country.

Lino Miani is a retired US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC. He also wrote this analysis of the assassination of Kim Jong Nam, an event that should, but is not, factoring into the willingness to engage Kim Jong Un diplomatically.

Lino Miani is a retired US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC. He also wrote this analysis of the assassination of Kim Jong Nam, an event that should, but is not, factoring into the willingness to engage Kim Jong Un diplomatically.

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and

Ligia Lee Guandique is a political analyst living in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Ligia has worked with human rights-based NGOs and

Nuno Felix is a former non-commissioned officer with Portuguese Army Special Operations Forces. He is a sniper and special reconnaissance expert and is currently working as a consultant to top executives in the financial sector.

Nuno Felix is a former non-commissioned officer with Portuguese Army Special Operations Forces. He is a sniper and special reconnaissance expert and is currently working as a consultant to top executives in the financial sector.