The Western media does not understand the bombings in Thailand.

On August 12, 2016, a series of thirteen bombs killed four Thai nationals and injured 35 people in the popular tourist towns of Hua Hin, Surat Thani, Phuket, and Trang. Thai officials claim this is a continuation of the Islamic separatist question in Thailand’s deep south, though the investigation is still underway. A quick search of articles about the bombings in Thailand will provide a myriad of articles that suggest the bombing is an indicator of an unpopular military regime or that Muslim extremism has spread throughout Southern Thailand. In reality, the bombings are just a small bump on the long road of conflict between ethnically-Malay Muslims of the Greater Pattani Region of southern Thailand and the Thai — Buddhist — controlled national government.

In a narrow sense, the bombings highlight a regional displeasure with the 2016 constitution referendum vote. More broadly, however, they emphasize the international community’s neglect of the substantive issue, specifically Thai ethnic policy that some researchers suggest has contributed to the deaths of nearly 7,000 people since 2004. The media, in search of a reason for the bombings that confirms Western bias against Islam, disregards the complicated geographical and historical context which drives this conflict. Thai ethnic policy, responsible for the creation of the Thai nation-state and its successful independence from Western colonialism, is paradoxically also the catalyst for unrest.

Context is Everything

Although the attacks threaten to affect one of Southeast Asia’s largest economies, Thailand’s greater problem is one of national unity. The Thai government believes the cohesion of the country rests on the strength of a national identity to unify the varied ethnic groups in peripheral regions where ancient historical relationships determined cultural identity. Until the 1850s, many people living within the boundaries of Thailand (or Siam) did not identify themselves as Siamese but rather by the identities of former kingdoms or villages. For example, some in the present North Region still identify with the Lanna Kingdom, while the Khmer Empire still influences the present East Region. Religion and mother-tongue, derived from these kingdoms, further shapes that dynamic.

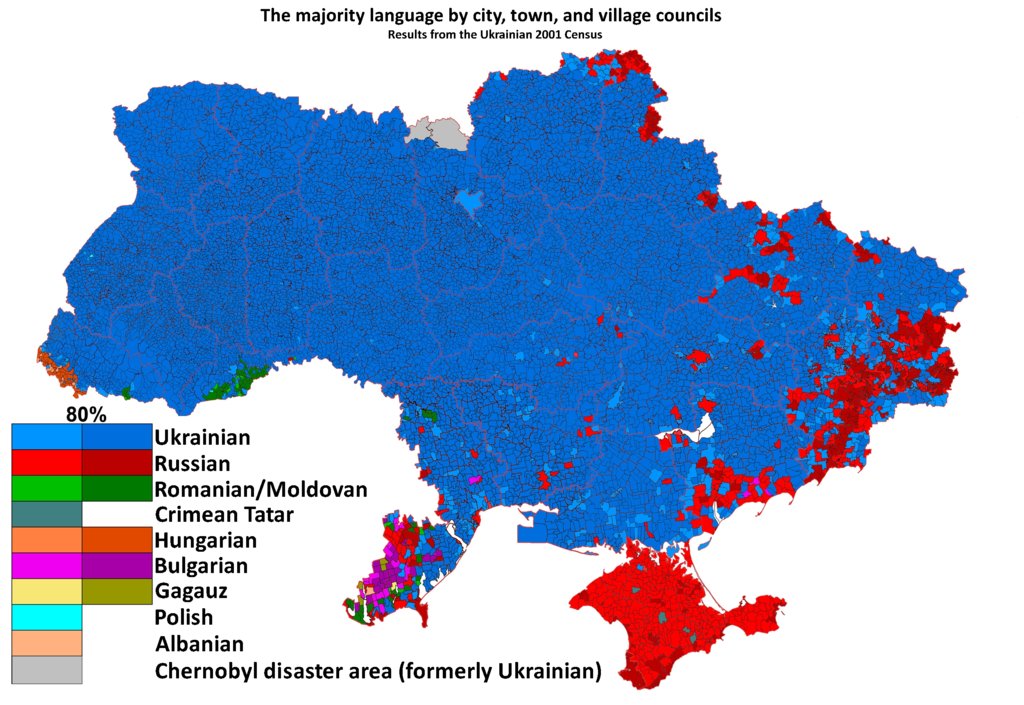

Like the other peripheral regions, the Greater Pattani Region is culturally and ethnically distinct from its Thai/Siamese neighbor to the north. In Greater Pattani, 83% of the population speaks Pattani-Malay (Yawi), while only 13% speak the Central Thai Dialect. The religious distinction of Greater Pattani is even more acute, with 94% of the population identifying as Muslim, forming an Islamic island in an overwhelmingly Buddhist Thailand. Historically a Muslim Sultanate, the Pattani Region paid tribute to the Siamese Ayutthaya Kingdom (1350-1767). The Pattani Sultanate maintained relative autonomy due to center-to-periphery distance from Ayutthaya and the Nakhon Si Thammarat mountains that physically isolate the region from the rest of Thailand. The series of Burmese-Siamese wars from 1547-1701 allowed the Pattani Sultanate to accumulate prestige and wealth as a regional trade center until the Chakri Dynasty of Siam subordinated the Sultanate in the 1700s.

European colonization drastically changed the political environment in Southeast Asia by the late 1800s. Fearing external influence, the Thai government, under King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), instituted a civic reform in 1906 that delimited provinces and districts and replaced local leaders with central government representatives that spoke only Thai. This reform sought to unify Thailand’s own ethnic identity through enforced standards of linguistic, educational, and religious behavior; standards that further alienated Greater Pattani. Though many Pattani-Muslims hoped to represent themselves in the newly-created Thai National Assembly, their participation was deterred by policies that required Muslim officials to have Thai names, prohibited their Muslim attire, enforced a nationalist curriculum in all school systems, and subjugated Islamic courts to provincial governors.

Missing the Target

The bloodless revolution of 1932 ended 700 years of absolute monarchical rule in Thailand, but was a missed opportunity for integration. Several social activist groups including Gabongan Melayu Pattani Raya — GAMPAR — (1944) and the Pattani People’s Movement — PPM — (1947) came into being in the politically turbulent aftermath of the Second World War. Tensions worsened in 1948 when approximately 1,000 Pattani-Muslims attacked Thai National Police forces at Dusun Nyor, Narathiwat resulting in the death of 400 attackers and 30 police officers. As Thai ethnic policy remained firm, Pattani-Muslims created more separatist groups including the Betubuhan Perpaduan Pembebasan Pattani (PULO) in 1968 and the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) in 1974, both of which relied upon violent attacks and assassinations to advance their separatist agendas.

Seeking to quell the violence from separatist groups, Prime Minister Prem Thinsulanond instituted a number of social programs, including the Southern Border Provinces Administrative Center (SBPAC) in 1981. Though these measures provided an outlet for grievances and were largely successful, local administrators heavily abused and misappropriated funding. In 2004, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, a northerner, terminated the SBPAC claiming the southern insurgency had mostly dissipated. SBPAC’s closure however undermined what leaders of the Pattani Region viewed as a social compact between them and the Prem administration.

A cycle of violence ensued. In January 2004, 30 Pattani-Muslim separatists attacked a Royal Thai Army (RTA) post killing four soldiers and stealing a large quantity of weapons. In response, Prime Minister Thaksin declared martial law and deployed 3,000 Soldiers that were ill-prepared for operating in the unique ethnic and linguistic landscape. Four months later, they raided the Krue Se Mosque in Pattani killing 32 suspected insurgents. Not long after, security forces killed seven demonstrators in Tak Bai. Seventy-eight others were crushed and suffocated during transportation to detention. The Prime Minister inflamed tensions when he controversially claimed their deaths were due partly to fasting during Ramadan. Insurgents responded in kind, beheading a Buddhist deputy village chief in Narathiwat and conducting other retaliatory attacks that encouraged the government to steadily increase troop numbers. Today, despite a twelve-year counterinsurgency campaign, 60,000 RTA troops and police now occupy the region of 11,000 square kilometers. Assassinations, ambushes, and improvised explosive device attacks occur regularly with no end in sight.

Prospects for Reconciliation

Despite displeasure towards government policies, relatively high voter-turnout rates suggest southerners still yearn to be part of the democratic process. Unsurprisingly, Greater Pattani presented the strongest opposition to the draft constitution in Thailand’s August 6, 2016 vote. In Yala, Pattani, and Narathiwat, most citizens opposed the new constitution due to concerns about Article 67, which allows the state to “promote and support education and propagation of principles to protect Buddhism”. For many Pattani-Muslims, this signaled a perpetuation of oppressive policies that began in the early 1900s. Reconciliation hinges on southern participation in the Thai National Assembly and reassurance or compromise regarding Article 67 of the Constitution.

A solution to this situation is not obvious and requires concerted effort to ensure that any accommodations for the south are in keeping with national interests. The Thai government must thoughtfully consider any concessions, such as granting autonomous status to Greater Pattani, that might result in the North and East Regions petitioning for similar concessions. A more successful approach may be the decentralization of the national government in order to allow the provinces greater opportunity to represent themselves — a major policy shift for a government with a strong preference for centralization. Proof of democratic commitment, and consequently Pattani reconciliation, hangs in the balance until the 2017 election. Until the Thai government takes deliberate but delicate steps to disentangle the conflict, flashes of violence will continue to disrupt development and discourage tourism and external investment.

Captain Caleb Ling is a U.S. Army Infantry Officer with combat experience in Iraq and Afghanistan, and extensive multinational training experience at the Joint Readiness Training Center. He is currently attending Chiang Mai University in Thailand.

Captain Caleb Ling is a U.S. Army Infantry Officer with combat experience in Iraq and Afghanistan, and extensive multinational training experience at the Joint Readiness Training Center. He is currently attending Chiang Mai University in Thailand.

The views expressed in the article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.