Feature Photo: Chengdu Global Center is the largest building in western China. It contains a mall, hotel, conference center, and water park.

Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in south-central China, is a lighthearted community. Famous as the home of the Giant Panda conservation program, Chengdu occupies an important place in the heritage of greater China. The attractive and prosperous city is also known for the beauty of its women, the spicy heat of its food, and the self-effacing sense of humor of its inhabitants. They will need it. In many ways, Chengdu is a microcosm of China’s rise and may also serve as a canary in the coal mine should the country’s experiment with capitalism begin to fall apart.

Founded during the warring states period by Lord Kaiming as a capital for his dominion, Chengdu means “Becoming a Capital.” With 15 million inhabitants and 3.87 million cars, the youth there sarcastically refer to it as “Becoming a Carpark.” The city’s traffic is indicative of the transformation that has affected China as a whole. Since the 1980s, an entire generation of rural Chinese has migrated to the cities looking for work in the new economy. Their flight has emptied the countryside, changed family dynamics across China, and forced a residential construction boom like the world has never seen. In Chengdu, the pace of change is so astonishing people joke they sometimes go to work in the morning and get lost on the way home because everything changes so quickly. The joke is not far from the truth.

Growth and Prosperity

The rapid transformation of China from a rural Communist backwater in the 1980s to the economic powerhouse of today is arguably the single greatest human endeavor since the Second World War. Since 1978, an estimated 800 million Chinese people have been lifted out of extreme poverty. China’s adult literacy rate in 2012 was 95.1% and climbing with youth literacy reaching 99.65%. Its infant mortality rate dropped from 4.2% in 1990 to 1.2% in 2012. Life expectancy in 2012 was 75.2 years, up from 69.5 years in 1990. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita increased an average of 9.3% annually from 1990.[1] In the space of a single generation hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens stopped having to worry about survival and became concerned about enjoying life. A Chinese version of the American Dream took hold in which young couples marry for love, own their own homes, and expect to retire comfortably without dependence on their children. This “Chinese Dream” once ignited, cannot be extinguished without calamity, forcing Beijing to seek resources to satisfy its growing industry and appetite for consumption.

China’s political aspirations have risen with its economic power. There is a sense at every level of Chinese society that after centuries of shameful disunity and perceived exploitation by outsiders, it is finally time to reclaim China’s place at the “center of the universe.” An air of inevitability and a disregard for short-term consequences now permeates Beijing’s foreign policy, but China lacks the cool confidence exhibited by Japan or Thailand, the only two Asian nations that were never colonized. Instead, China bullies its neighbors with incomprehensible urgency. Shamelessly and without hesitation, Beijing attempts to divide and conquer in political and economic matters, raising the level of uncertainty in the region and leaving little doubt it will act militarily if required. East and Southeast Asia are regrettably vulnerable to this approach, leaving only the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the US system of alliances to thwart Chinese hegemony in the region. In this way, the US Navy’s 7th Fleet is the ultimate regulator of China’s military, economic, and political aspirations—and this makes Beijing restless.

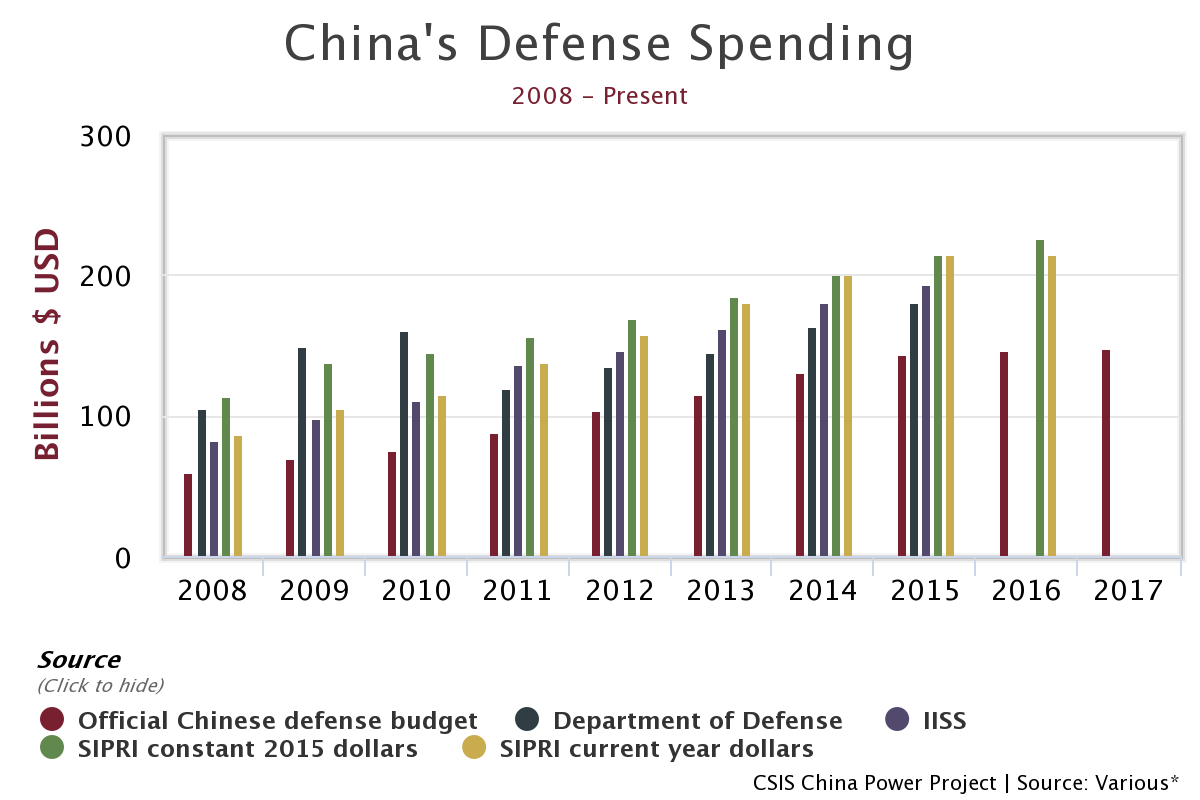

In response, China’s military expansion is almost as astonishing as its economic growth. Since 1989, the budget of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has increased an average 9.56% per year though some estimates put the figure much higher.[2] China has the luxury of focusing its military efforts against a single paradigm: the United States Military. In pursuit of parity, the PLA has acquired nuclear weapons, carrier and stealth aviation, modern command and control systems, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and special operations capabilities. Some believe the Chinese may actually lead the world in cyber, anti-ship ballistic missile technology, and even quantum computing—a capability that could obviate any attempt at communications security. Though the United States Military is a large and robust rival, China’s drive for parity requires only that it learn from the Pentagon’s successes and avoid its mistakes. Accordingly, Chinese officers miss no opportunities to study America’s weaknesses and develop countermeasures. For them, parity is only a matter of time and persistence, something the Chinese are more comfortable with than Americans are. It is not surprising then that the PLA is not just a military force, it also carries political and economic weight within the Chinese system.

China’s Future: Unite or Ignite?

Unfortunately, China simply cannot sustain the economic growth required to keep it all going. The problem is dire. Even a moderate reduction in the pace of growth will profoundly affect tens of millions of workers. If a contraction stratifies and unbalances China’s economy, the country’s fractures will begin to re-emerge. Income and quality of life will become a matter of struggle between ethnic groups and geographic regions. China’s coastal cities are extremely important to its economy; those in the interior are less so. Profound cultural differences exist between those from the north and those from the south as well as between east to west. Xinjiang and Tibet already dream of an independent future as do some in Hong Kong and of course Taiwan. Igniting rebellion in these places requires only a spark. More profoundly, if the Chinese economy stagnates, there is simply no way to keep 600 million military aged men busy, unified, and politically obedient without expansion and conquest. Economics may thus force China to decide between conflict at home and conflict abroad.

China’s Communist Party leadership is already preparing for this eventuality. Efforts to control information and stamp out dissent serve to inoculate the country against the centrifugal forces that threaten to spin it apart. The PLA appears to have three principal goals: develop a power projection capability, use that capability to solidify control of energy supply lines, and build positive relationships with the Chinese people through disaster response. China recognizes it will need all these things if it decides to embark on a policy of conflict overseas. Though at the moment Beijing pushes its territorial ambitions incrementally, it openly experiments with hard power solutions in the South China Sea, the East China Sea, and elsewhere. Any disruption in the quality of life in Chinese cities like Chengdu may provide an early warning as to whether Beijing will militarize its foreign policy. In the lengthening list of things that Chengdu is becoming, perhaps “canary in the coal mine” is the most significant.

[1] Statistics from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

[2] Figures in constant 2015 US Dollars. Raw data analyzed from the SIPRI database. SIPRI’s data typically exceeds official Chinese government statistics that are believed to be underreported.

Lino Miani is a retired US Army Special Forces officer, author of The Sulu Arms Market, and CEO of Navisio Global LLC.